A Powerful Way to Explore Possible Identifications

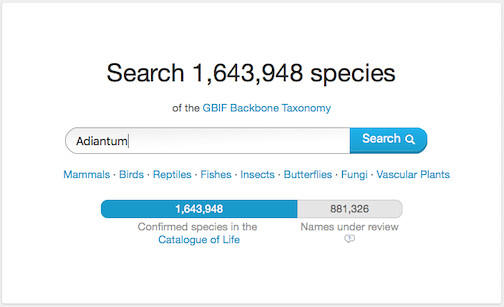

With some prompting by @billdodd, I have once again started using the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (www.gbif.org) to help with identifications of my iNat observations. Because of the massive size of their database (1.6 million species; 700 million occurrences), it offers a vast network of possible natural history occurrences through which to search. Then, combining their search results with an image search on Google Images offers a quick visual check of possibilities. This one-two punch is often sufficient to narrow an identification considerably and often nail it exactly. This is particularly true for groups of organisms or particular areas which may not be well-represented in the iNat database or other common resources.

But there’s a problem: How to do you narrow a search in such a huge database like GBIF? I have found it particularly powerful when I can begin by limiting my search parameters to a certain family or genus (of plants, for instance). The combination of a “species” search (which can be tailored to a family or genus) and the mapping capabilities of GBIF can really help you zoom in on likely possibilties. Here is an example from my recent efforts:

A Maidenhair Fern from Chiapas:

In January, I photographed a maidenhair fern in dry oak-pine woodland in the mountains surrounding San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico:

http://www.inaturalist.org/observations/5066655

I knew that there were several species in Mexico. A quick search of the iNat database alone indicates at least 13 species in Mexico:

http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=6793&taxon_id=48436&view=species

Even selecting for just the state of Chiapas indicated at least four possibilities:

http://www.inaturalist.org/observations?place_id=97003&taxon_id=48436&view=species

but there were only four iNat observations of the genus from that state so that limited my confidence in this comparative set.

So I went to the GBIF database: www.gbif.org and did this: From the home page, under the “Data” menu at the top, I chose “Explore Species”:

This brings up a simple search field: http://www.gbif.org/species. Next, I typed “Adiantum” into the search field. (I didn’t bother to limit my search to “Vascular Plants” although I could have.)

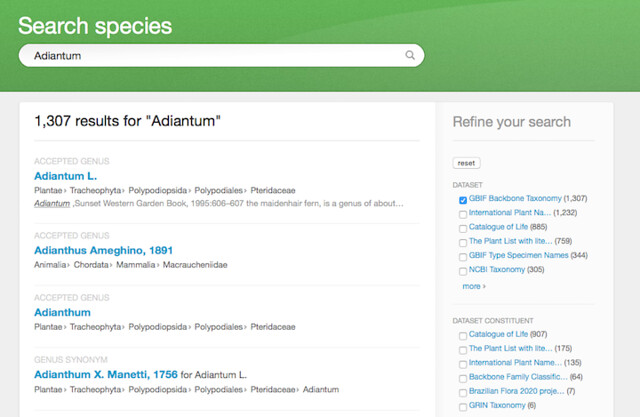

The subsequent search results gave me 1,307 results for “Adiantum”, the very first one of which is the one I'm interested in: “Accepted Genus, Adiantum L.” Make sure you find the one you want; you may also see other names labeled "Doubtful Genus", "Doubtful Species", "Species Synonym", etc. Sometimes the family or genus name may have two different entries spelled the same but with different original authors. You'll always want to pick the "Accepted ..." of whatever your focused on. A taxonomic classification listed under the name also helps to make sure you're in the right group of organisms; notice in the screen capture below that there is a genus of mammals spelled "Adianthus"!

Ignoring all the ways to “Refine your search” (right hand panel), I just clicked on that first result for “Adiantum L.” That brings up an Overview page.

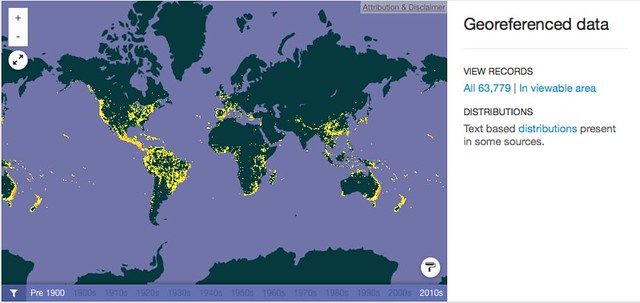

Below the Overview box you’ll find a map of the world. Next to the map, it indicates that this search found 63,779 georeferenced data points.

Adiantum is distributed on all continents except Antarctica. The next step offers the most powerful capability: Just zoom into the area of interest! (With the little roller brush icon in the lower right of the map, you can choose among various views such as Classic, Night, Terrain, Satellite, High Contrast, or Roads. Since I am a Google Earth fanatic, I often choose Satellite, but “Roads” is also useful where I need to navigate to my location by that means. As you zoom, the specimen dots may seem to disappear--they are probably just too small. When that happens, go to that handy "paint roller" icon again and choose a larger point size.) So I zoom and zoom and zoom, until I’m looking at just the area around San Cristóbal de las Casas, in the middle of Chiapas:

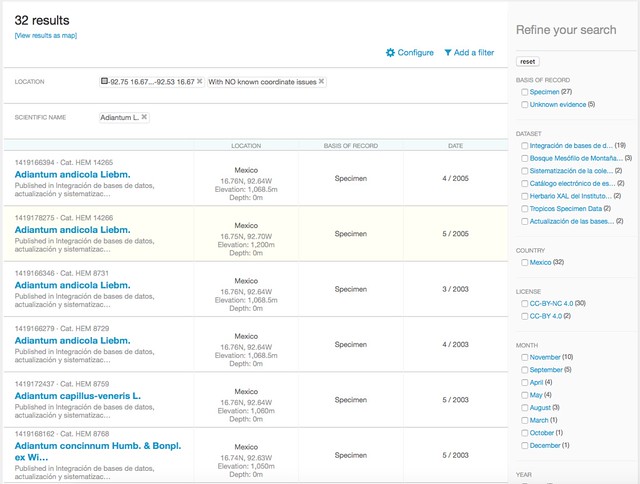

Then clicking on “In viewable area” in the right panel of the map brings up a list of all those georeferenced data just in my area of interest--that is, just the area I've zoomed into. A portion of that list is shown in this screen capture:

Again, the "Refine your search" panel on the right side would allow me to subset this group of specimens more if the number of returns was still too large or if I want some other refinement. In this case, I don't need to, since I have narrowed my possibilites from 60,847 records to just 32 records. This represents 32 museum specimens of Adiantum collected through the years right around San Cristóbal! Scanning down the list, I find that five species of Adiantum have been collected there: A. andicola , A. braunii , A. capillus-veneris , A. concinnum , and A. patens. In actuality, an even closer zoom into San Cristóbal—where a lot of botanical collecting has been done—narrows my search to just andicola, capillus-veneris, and concinnum, and of these the first is the most numerous in the database by far.

Now I can open a new tab in my browser and have Google Images ready. A quick search through each of the three relevant Adiantum’s shows that my photos (especially the view of the underside of the fronds) is a good match to only Adiantum andicola. And I have my ID!

A few caveats with this method:

— No database is complete, even GBIF. Depending on how specific an area you zoom to on the map, there may or may not be a good selection of specimens. So gauge your zoom area to get a reasonable set of possibilities. If you zoom in too far, you may miss all records or you may accidentally exclude relevant ones. If your area of interest has no specimens right near it, back out to encompass the nearest county or state to gather more records. And keep in mind that you are widening your search, so the precise species you find in that larger area may or may not occur where you were.

— No database is infallable. There are always the possibilities of mis-identified museum specimens, or changes in taxonomy not reflected in the GBIF search. [In particular, see the link to @rdmpage's blog in @kueda's comment, below.] Related to this, Google Images is a great resource for finding images of species, but it is often very “inclusive” when grabbing images off the internet, especially when it can’t find your specific search target. When scanning through Google Images, ALWAYS check the description and/or go to the original page to double-check that the pic your looking at matches what you searched for.

–– Interestingly, GBIF taps into iNaturalist observations. If any meet your criteria and geographic area of interest, they will show up in your search results. That's a double-edged sword: Good for seeing local iNat observations along with specimen records, but Bad because of the potential pitfalls we are all familiar with using crowd-sourced identifications. In that helpful right-hand panel to "Refine Your Search", you can include or exclude "Human Observations" (where iNat observations fall); by default they are included.

— Most importantly, keep in mind that photos may not be sufficient to make a solid identification. This may be due to the technical details of how similar species are distinguished and/or it may be due to the quality of your photos. You can always help your cause by photographing all the important parts of a plant or critter. For plants in particular, it’s not always obvious what characters will help distinguish one species from another, and those characters may or may not be visible in a set of photos. Be sure to photograph the whole plant, the leaves, the flowers and fruit if present, and get good close-ups at various angles. This might includes top and side views of flowers (e.g. for Composites), views of the underside of leaves, etc., etc. If you’ve ever worked through dichotomous keys for a given group of organisms, you’ll have some sense of the characters to emphasize in images; this just comes with experience. If you have some science training, a little supplemental research with something like Google Scholar, Archive.org, or JSTOR may point you to useful technical papers to help with your ID. A particularly useful link to the Biodiversity Heritage Library is found in the right-hand panel of the Overview window in the search results on GBIF. That will bring up a list of very specific references to your species of interest; you can dive into that rabbit hole and follow it ad infinitum.